We’re pleased to bring you a guest post on a recent Supreme Court order where certain offences under the Copyright Act were held to be cognizable and non-bailable. The post is co-authored by Akshat Agrawal and Sangita Sharma. Sangita is a 3rd year student at Gujarat National Law University and has written for us earlier here. Akshat is a lawyer currently litigating at the Patna and Delhi High Courts. He has written for us earlier here.

The Supreme Court’s Unsettling Attempt at Settling the Debate on Section 63 of the Copyright Act

Akshat Agrawal & Sangita Sharma

The questions that matter

On the 20th of May, the Supreme Court, in M/s Knit Pro International vs The State of NCT of Delhi & Anr, held that offences under Section 63 of the Copyright Act, 1957 are cognizable and non-bailable offences. This basically means that the police can proceed to register an FIR and arrest anyone against whom there is an allegation of (a) knowingly committing or abetting copyright infringement; (b) knowingly violating any other rights granted under the Act, without the need of a warrant. Further, the person(s) so arrested cannot be released from custody as a right and would have to apply for bail before a court of law to be considered under Section 437 and Section 439 of the CrPC,1973 as well as the provision of anticipatory bail, i.e., Section 438 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC). In this post, we analyse this decision of the Supreme Court and point out several issues we have identified with the order.

Earlier posts on SpicyIP have also extensively covered this issue of the interpretation of Section 63 here, here, here. Here are the decisions where various High Courts have taken conflicting views:

| Case Name | High Court | Decision |

| Jithendra Prasad Singh v State of Assam, 2002 | Gauhati | Cognizable and Non-Bailable |

| Amarnath Vyas v State of A.P., 2006 | Andhra Pradesh | Non-Cognizable and Bailable |

| Abdul Sathar v Nodal Officer, Anti-Piracy Cell, Kerala Crime Branch Office & Anr, 2007 | Kerala | Cognizable and Non-Bailable |

| Sureshkumar S/o Kumaran v the Sub Inspector of Police, 2007 | Kerala | Cognizable and Non-Bailable |

| State Govt. of NCT of Delhi v Naresh Kumar Garg, 2013 | Delhi | Non-Cognizable and Bailable |

| Deshraj v State of Rajasthan and Anr, 2017 | Rajasthan | Cognizable and Non-Bailable |

| Anurag Sanghi v State & Ors, 2019 | Delhi | Non-Cognizable and Bailable)

(Overturned) |

| Nathu Ram v State of Rajasthan, 2021 | Rajasthan | Cognizable and Non-Bailable |

| Piyush Subhashbhai Ranipa v The State of Maharashtra, 2021 | Bombay | Cognizable and Non-Bailable |

| ANI Technologies Pvt. Ltd. v State of Karnataka, 2022 | Karnataka | Cognizable and Non-Bailable |

The Judgment

The Supreme Court was dealing with a case where “Knit Pro” registered an FIR against Anurag Sanghi (Respondent No. 2), for offences under Sections 51, 63, and 64 of the Copyright Act, read with Section 420 of IPC, 1860. An application under Section 482 of the CrPC was filed to quash the said FIR, and the criminal proceedings initiated thereof before the Delhi High Court. The contention in the application for quashing was limited to the argument that the offence alleged was “non-cognizable” and “bailable”- where the correct modus was to file a complaint before the concerned magistrate seeking permission to initiate an investigation.

Allowing this application, the High Court held that offences under Section 63 had to be non-cognizable due to the decision of a coordinate bench in Naresh Kumar (supra) and the decision of SC in Avinash Bhosale (supra). The SC in Avinash Bhosale (supra) held offences prescribing a punishment “upto” 3 years and not “more than 3 years” as non-cognizable and bailable offences as they would fall within item 3 of Part II of Schedule I of the CrPC. The High Court stated that although Avinash Bhosale did not carry much reasoning due to the identical punishment prescribed in Section 63 and Section 135(1)(ii) of the Customs Act, 1962, it was binding.

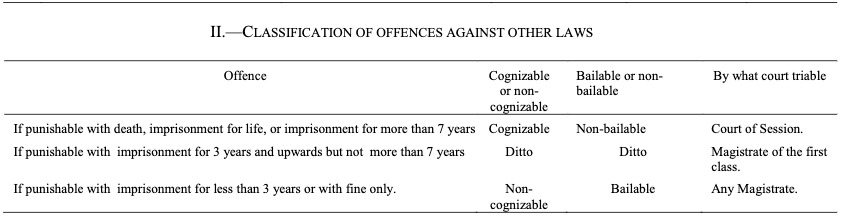

The Supreme Court, on appeal, noted that the punishment prescribed under Section 63 extends upto “three years.” It held that only if the prescribed punishment is “less than three years” does the offence become non-cognizable and bailable. It further held that even if the offence prescribes punishment of a term of “three years or more,” ( including a period of three years), the same would, unambiguously, fall within Item-2 of Part-II of the First Schedule to CrPC, and thus be cognizable and non-bailable.

Missed Points

The Supreme Court, by not looking at the Copyright Act as a whole and by ignoring provisions that have an important bearing on the interpretation of Section 63, in our opinion, has endorsed criminality in a very problematic way. Some of our critiques of the order are as below:

Interpretive issues

As seen above, the offences punishable in the range of 3 to 7 years are classified to be Cognizable and Non-Bailable according to item 2 of Part II of Schedule 1 of the CrPC. However, Section 63 provides the extent of punishment for offences to range between 6 months to 3 years. The Supreme Court only considered the upper limit of 3 years, which seems to fall within the range contemplated in Item 2, and simply ignored that punishments can also possibly be for less than 3 years- something not contemplated for offences that fall within Item 2. Thus, effectively, it relegated offences that are ultimately punished for less than 3 years to also be those which fall within Item 2 of Part II of Schedule-1 of the CrPC, deeming them to be cognizable and non-bailable-something which the legislators resisted by specifically providing an Item 3. For instance, sampling copyright music for your show could lead to you being arrested! Moreover, there are offences within the IPC which are punishable for up to 3 years, yet non-cognisable and non-bailable (Sections 181 and Section 193).

With conflicting decisions on the issue by various HC’s in the context of the Copyright Act, and the Supreme Court in the context of the Customs Act, which has a verbatim provision (also 2 judge bench), in Avinash Bhosale (supra)), we believe the Court ought to have considered and engaged with their rationale. Further, the Supreme Court could have at least applied the Rule of Lenity rather than holding the provision “unambiguous.” For starters, here is an ambiguity- Could an offence where the ultimate punishment prescribed is possible to be less than 3 years be a cognizable and non-bailable offence?

Moreover, Section 64 of the Copyright Act shows that on an action of seizure, the police officer can “seize copies of infringing works without a warrant.” No such waiver of the requirement of a warrant has been explicitly prescribed under Section 63, given the liberty of an individual is at stake there.

Intention of the Legislature

Under the Trademarks Act, 1999, the legislature has explicitly mentioned that offences under Section 103, 104, and 105 of the Trademark Act, which may extend upto three years are cognizable offences (under Section 115(3)). This explicit mention shows that the legislature specifically intended to make an exception to the general principle that such offences would generally not be cognizable, lest it need not have mentioned the same. No such mention finds a place within the Copyright Act which uses a verbatim penal provision.

Inadvertent Delegation of Judicial Power to Police

The proviso to Section 63 encapsulates a situation where a punishment of even less than 6 months can be imposed if the infringement is not in the course of trade and business. The Supreme Court’s decision renders, even this situation, where there is no possibility of a punishment of 3 years, to be cognizable and non-bailable. Are the law enforcement officials supposed to determine the fine line where an infringement might not be in the course of business or for non-commercial purposes? A blanket order, as currently given by the Supreme Court, does complete injustice to the intended purpose of this proviso, as well as the Explanation which specifically contemplates some infringements to not be offences within this Section.

Exemptions and Limitations to Copyright and its Infringement

As one of us had noted elsewhere earlier, elevating section 63 to be cognizable and non-bailable gives authority to the police to arrest and curb liberty without even judicially determining whether the use is actually infringing or permissible. This dilutes the consideration of exemptions and limitations to Copyright prescribed under Section 52 of the Copyright Act. Can the police be expected to figure out whether a use by an alleged infringer is permissible under Section 52? Moreover, in light of pronouncements of the High Court holding the American 4-factor test of fairness to be applicable or pronouncements holding even commercial uses to be potentially “fair,” there seems to be no reasonable way in which law enforcement officials can be expected to figure out whether use is infringing or permissible under the Copyright Act. The Delhi High Court, in the context of Section 64, in Event and Event Management Association v. Union of India (2012) 52 PTC 380 (Del) (2nd May 2011), had held that even while seizing goods, if a defence under Section 52 is taken, the members of law enforcement ought to satisfy themselves that such defence is untenable- given seizure could be effected without a warrant and without immediate cognizance by a magistrate in Section 64 as against arrest. Can the judicial opinion of law enforcement agencies be the basis for curbing the liberty of individuals?

Permissible uses under Section 52 find their genesis under Article 19 of the Constitution of India. Potentially arresting individuals who might be using works for permitted purposes seems completely inconsistent with the intention of the legislature, which carefully curated a balance within the Copyright Act. In other words, keeping even one legitimate user in judicial custody inspite of the use ultimately being consciously permissible could immensely discourage exempted uses like criticism or research. Weren’t permissible uses of works like criticism, research, etc. supposed to be encouraged?

Power, Pride and Prejudice (but to whom?)

This judgment already paves way for the cash flowing copyright industries, with deep pockets, to weaponize copyright and use threats of penal action even against legitimate users. Without the registration requirement, there is no need of any documentation to even claim ownership, before pointing at someone else for alleged infringement and opening them up to arrest. What’s to stop an empty claim of ownership, to threaten and rescind legitimate uses, merely due to the possibility of them being potential licensing revenue? This is not even a presumptive argument- it has done this in the past by organisations who didn’t have the rights they were claiming to have. (see here, here, and here). While the court is willing to make Section 63 cognizable and non-bailable, are they also willing to make Section 60 (groundless threat of legal proceedings) cognizable and non-bailable? We certainly don’t advocate it, but it would at least balance the power scales!

Decriminalisation

On this blog, various authors have extensively critiqued the criminalization of copyright infringement, specifically in the context of the misconstrued marriages of IP and property, theft and piracy, as well as continued ignorance of users’ claims due to overzealous enforcement attempts of copyright industries. Nikhil also criticized criminalization due to the potential of weaponizing copyright (as was recently done by the Beverly Hills police) for targeted action against vulnerable groups and to silence criticism. However, these provisions are often justified for their “deterrent” value.

Well, it seems this judgment has paved the way for a lot of deterrence, including deterring a user from using copyrighted works even for permitted purposes, which finds its genesis under Article 19(1) of the Constitution, lest one wishes to find themselves behind bars. Would this be constitutional?

The authors would like to thank Swaraj Barooah for his valuable inputs on this piece.