Continuing the discussion (see here for Part I) on the Delhi High Court and the Supreme Court’s 2023 Keywords decisions, Malak Sheth critiques the Courts’ approach, arguing that use of a trademark in digital world cannot be viewed from the same lens of assessing their use in the physical world. Malak is a third year law student from Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law, Punjab. For the interested readers, the Delhi High Court’s division bench decision in Google v. DRS has been discussed here and here on the blog. The Supreme Court’s order in MakeMyTrip India Private Limited v. Google LLC has been discussed here.

Reconceptualizing Trademark Protection in the Digital Age: A Proposal for Reform in Response to Google Ads’ Policy- Part II

By Malak Sheth

This is Part II of the two-part post on the issue of the use of trademarks in the Google Ads programme and the decision of the division bench of the Hon’ble Delhi High Court in the Google LLC v. DRS Logistics and the Hon’ble Supreme Court decision in MakeMyTrip India Private Limited v. Google LLC (“the cases”). This part critiques the approach of the Hon’ble Courts in the cases by propounding that the challenges of the use of trademarks in the digital world are not the same as those in the physical world.

Trademarks In The Digital World: Its Vindication as a ‘Property Mark’

The first part of this piece indicated how diverting the traffic from the website of the owner to that of the advertiser through the Google Ads programme when coupled with factors such as consumer obliviousness and behavioural psychology, could amount to passing off. It drew support from the judgement of the single-judge bench in the case of DRS Logistics v. Google before it was overruled by the Division Bench.

Even if it might be conceded that the consumer is not deceived at the time of making the purchase, it cannot be overlooked that at the time of clicking on the advertised webpage, the confusion was persistent. In such a case, the doctrine of ‘initial interest confusion’ supports the claim of passing off and will be dealt with later in this piece.

Now, for instance, Funzo, a Quick-Commerce (“Q-com”) platform, could be imagined as having spent considerable resources to ensure that if a consumer in India thinks about getting food delivered within a few minutes, they look for Funzo. At the same time, Pepto, for example, does not spend on offline campaigns for this association of Q-com with its trademark but bids the highest for the keyword ‘Funzo’ on Google ads which ensures its position on top of the Funzo website on the SERP. It would be a case of ‘unfair competition’ to allow Pepto, in such a scenario, to pass off its Q-com services through Google Ads. This is because in a case where the consumers had themselves associated Q-com with the Funzo trademark and had this association been unreal, they would have simply searched for ‘Quick Commerce’ platforms in India.

The Court in the DRS case dismissed DRS’s passing off claim, stating that using its mark as a Google Ads keyword did not cause confusion since the marks were not deceptively similar. It also referenced examples from physical stores, like a retailer pushing a Lenovo laptop instead of a Dell one, to argue ‘there is nothing illegal in seeking out such internet users as targets for advertisements that they may find relevant’.

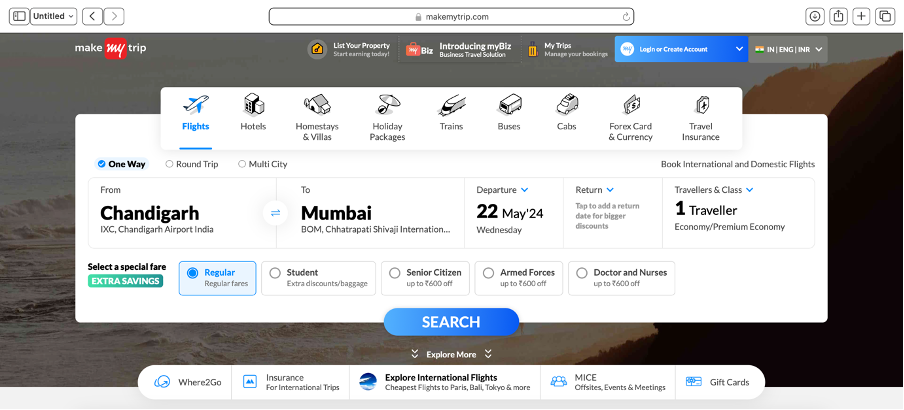

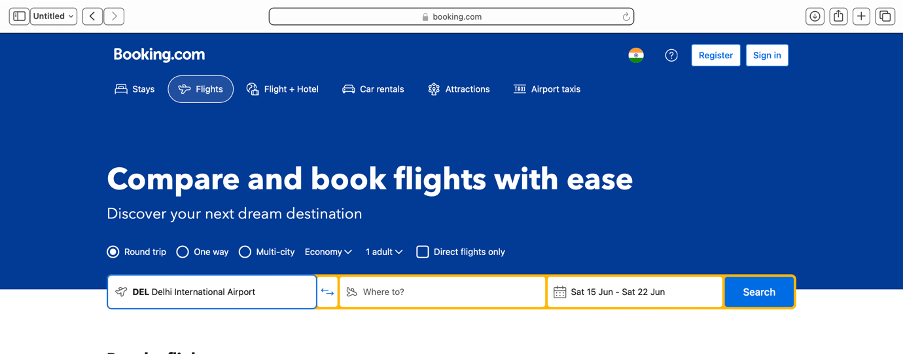

However, this can be negated by treating it as an instance of the classical logical fallacy of comparing the non-comparable. In the example wherein the retailer promotes the Lenovo laptop in place of the Dell laptop, the consumer is conscious of the retailer’s tactics and any decision that they arrive at is a result of this consciousness. However, this aspect of consumer consciousness is particularly missing in the case of redirection as a result of Google Ads. In this case, the website is tailored to showcase the most dominant aspect of its services, for example, online travel intermediaries such as MakeMyTrip and Booking.Com, showcase their conspicuous search box which seeks inputs for dates for travel; online marketplaces showcase their range of offerings and so on. It is commonly noticed that the trademark/brand name is relegated to the corners with smaller fonts which is the primary cause of consumer obliviousness (see below). This is because of the practices used for consumer engagement coupled with the lack of positive incentive for the consumer, which is discussed further in this article, to make an active effort to go back to the mark they searched for.

Trademarks in the Digital World: Use of Smarter Technology for the Smart Humans

The Court in the DRS case noted that assuming an internet user is solely seeking the address of a trademark proprietor during a search is flawed. It explained that users might also seek reviews, competitor information, or other brand-related details. However, the Court overlooked its own observation regarding Google’s ad ranking system, which relies on an Artificial Intelligence (“AI”) system monitoring user intent to determine ad placement. This means ads are shown based on their relevance to the search query, as determined by the quality score of the sponsor’s website. For example, if a user has previously searched for travel destinations and then looks up MakeMyTrip, it’s likely they intend to visit the site for bookings. Since Google earns revenue based on the Click Through Rate (CTR), which measures how often users click on ads, the AI prioritizes ads with higher CTR. Therefore, real-time monitoring of user intent through AI renders claims of innocuous searches ineffective against the ad program.

Further, it also negated the doctrine of ‘Initial Interest Confusion’ that propounds infringement liability even if the alleged infringement causes temporary confusion in the minds of the consumers. The doctrine can be best understood by the metaphor used by the United State’s Ninth Circuit Court in Brookfield Communications, Inc. v. West Coast Entertainment Corporation. The Court provides an example of a misleading road sign of West Coast’s Competitor (for example “Blockbuster”) on the Highway which says “West Coast Video: 2 miles ahead at Exit 7” even though West Coast is actually situated at Exit 8 while Blockbuster is positioned at Exit 7. Customers seeking West Coast’s store will exit at Exit 7 and search for it, only to be unable to find it. However, upon seeing the Blockbuster store conveniently positioned near the highway entrance, they may simply decide to rent from there.

The Court in the DRS case appears to have been swayed by the criticisms of this analogy that in the case of web browsing, the internet user could, by the click of a button, exit from the site on which he had landed without any inconvenience. This is because it held that mere generation of interest in the sponsored link without any likelihood of confusion cannot be made liable under the doctrine of ‘Initial Interest Confusion’.

However, the Court in arriving at such a decision has failed to recognise that consumer behavioural psychology explicates that the motivation of a consumer to take positive actions depends on the resultant performance of their efforts. This means that the incentive to make a positive effort depends on the benefit analysis of making the decision which usually hinges on the resemblance or distinctiveness of the result after having made a positive effort to the user’s expected end result without the same. Therefore, in a situation wherein, for example, a user mistakenly lands on Flipkart instead of Amazon to buy Nescafe coffee, they are unlikely to switch sites due to lack of incentives, despite the convenience of going back in a single click. Websites often use clickbaits and dark patterns to manipulate users into making unintended purchases. Even when that is not the case, websites often employ clickbaits and at times dark patterns to enhance consumer interaction and seduce/force them to make a purchase that they otherwise would not have. At this juncture, we must not lose sight of the reason of the consumer having landed on the website in the first place which is as a result of the ‘initial confusion’. The real-life equivalent of the same would be when brands list authorized service centres for at-home device servicing, consumers often prefer the first option despite others being readily available on subsequent pages, as the outcome remains consistent.

Conclusion

The analysis in the foregoing paragraphs highlights the problem with the approach of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the MakeMyTrip case wherein it refused to provide interim reliefs to MakeMyTrip based on the ratio in the DRS case. The economic justification of Trademarks is also to reduce the “search costs” of the consumers and the Google Ads programme militates against the same if the consumers have to keep looking out for the correct domain. Further, allowing third parties to piggyback on the associative value of the goods and services to a particular trademark created through extensive advertisement also reeks of unfair competition. It is unfair to fraudulently divert the clientele of another for one’s benefit and therefore should not be allowed. As a consequence, Google Ads should not be allowed to use trademarks as keywords and should be mandated to follow the same policy of not allowing the same, as it does in the European Union, for India.