We’re pleased to bring to you a two-part guest post by our former blogger Rajiv Choudhry, discussing the recent Delhi High Court order granting an anti-anti-suit injunction in favour of InterDigital. Rajiv is a practicing advocate based in New Delhi. He specialises in IP law, with a focus on high – technology and patent law and advises/represents clients on SEP/FRAND and other issues related or unrelated to those discussed in the post. He’s also a founder member of the Fair Standards Alliance, a not-for-profit body that advocates fairness in patent licensing. The views expressed in the post are personal. Rajiv’s previous posts on the blog can be viewed here, here, here, here, here, here and here.

India’s First Anti-Anti Suit Injunction (A2SI) Order: A Missed Opportunity (Part II)

Rajiv Choudhry

Delhi High Court

In Part I of this post, I’d covered the decision issued by the Wuhan Court and includes a comparison of the prayers (as stated by the DHC) made in the Wuhan suit and in the patent infringement suit at the DHC.

This post continues from the previous post on the issue and covers a critique of the decision of the DHC and various factors that have been overlooked by the court in issuing the first A2SI. These factors include InterDigital’s history in Chinese courts, and before Chinese anti-trust authorities.

Para 98 provides the conclusion: “Holistically viewed, I do not think that the Wuhan Court was justified either in holding that the plaintiffs had sought to interfere with the complaint filed by the defendants in the Wuhan Court, by filing the present suit, or that they intended to exclude the jurisdiction of the Wuhan Court thereby.”

This reasoning provides a higher pedestal to the patentee, and the alleged infringer is left to bear the brunt of the order. How can InterDigital be entitled to a FRAND royalty before determining: validity, essentiality and / infringement of each of its patents? Isn’t a court entitled to hold specific views about the lis it is approached to adjudicate upon? It is reasonable for the Wuhan court to view the Indian filing as an impediment in the final determination of global FRAND rates.

The matter in India is one for determination of damages. Here it must not be forgotten that in patent matters: damages come at the end of a trial, where the Plaintiff has shown that it has a right, that right has been infringed, and that claimed damages will make it whole – i.e. are in proportion to the Plaintiff’s losses. Even assuming that InterDigital’s patents are: (1) Valid, (2) Essential, and (3) Infringed, all that InterDigital is entitled to is a FRAND royalty (see para 7). The question whether the demand is FRAND is itself a question that, as para 7 provides, is up for deciding. Despite recording this fact (last sentence) in para 98, the order does not factor the same into consideration.

Once a different court is seized of the same matter (determination of FRAND royalty / global royalty), the Delhi Court should have gone slow as itself observes the Supreme Court’s order in Modi Entertainment Network v. W.S.G. Cricket Pte Ltd. (para 23, page 24) and the seven principles it laid down for issuance of an anti-suit injunction.

In particular, the present order loses site of the fact that global royalty rate determination is up in Wuhan (para 97) and that a confidentiality agreement is already in place between InterDigital and Xiaomi in 2016 (para 97). The court also loses site of the fact that the Wuhan matter is for a global royalty rate determination, which includes India. Hence it is India that is a forum-non conveniens, not China.

Sufficient to state that once the Wuhan court sets a global rate, there would no requirement for any court leave alone the Delhi Court to determine validity, infringement, essentiality, etc.

However, reasoning in para 99 loses site of this fact and presumes that the Indian court will set out to do all that at least for the patents in suit, no matter that it has to reach the same result that the Wuhan court is tasked with.

Hence the court wrongly concludes that the Wuhan Court order of 23.09.2020, “…falls into error falls into error in opining that the plaintiffs had, by initiating the present proceedings before this Court, sought to exclude the jurisdiction of the Wuhan Court. Rather, the Wuhan Court has, by its order, sought to exclude the jurisdiction of this Court to adjudicate on the lis brought before it by the plaintiff which this Court, and no other, is empowered to adjudicate,…” The order also concludes that there is no overlap / minor overlap between the two matters, which does not prevent it from adjudicating the same.

The Court in issuing its order also provides that if the Wuhan court enforces its ASI order, and directs InterDigital to deposit penalties for prosecuting its Indian suit, then Xiaomi must compensate it by depositing a corresponding amount with the Court in India. This amount could be secured by InterDigital thereafter.

This is an entirely wrong conclusion and the order makes no reference to the advanced negotiations held into by the parties. The Delhi High Court order makes selective reference to the Wuhan court order and does not refer to the substantive facts / reasoning therein.

If one reads the Chinese court order, it is clear that InterDigital is forum shopping and using one court to issue orders to avoid those from a different jurisdiction.

Some aspects that should have been considered by court (or should have been brought to the attention of the court but were not:

A. InterDigital in Chinese Courts

The DHC does not keep in view the conduct of the parties: In 2013, InterDigital did not participate in antitrust proceedings brought in by Huawei in China for the fear that its executives would be arrested. Shenzhen-based Huawei claimed InterDigital charged it a royalty rate far above what it obtained from Apple Inc and Samsung Electronics Co Ltd. See post on reuters on this issue and InterDigital’s own SEC filing.

This proceeding was a result of the suit that InterDigital had brought against Huawei and others in the U.S. International Trade Commission for infringing its SEPs on 26.07.2011. And very predictably on 05.12.2011, Huawei filed a suit against InterDigital in Shenzhen Intermediate Court in China. This suit alleged that InterDigital held a dominant market position in China and the United States in the market for the licensing of essential patents owned by InterDigital and had abused its market power by engaging in unlawful practices, including differentiated pricing, tying, refusal to deal, etc.

On 04.02.2013, the Shenzhen Court held that InterDigital had violated China’s Anti-Monopoly Law by (1) seeking royalties from Huawei that the court believed were excessive, (2) tying the licensing of essential patents to non-essential patents, and (3) requesting as part of its licensing proposals that Huawei provide a grant-back of certain patents to InterDigital. The court ordered InterDigital to cease the alleged excessive pricing and bundling of non-essential patents with essential patents and pay Huawei approximately USD3.2 million in damages.

InterDigital appealed to the Guangdong High Court, which affirmed the Shenzhen Intermediate Court’s decision in its entirety. The High Court found the two acts of InterDigital to constitute an abuse of its market dominance. See coverage here and here.

B. InterDigital’s history with Chinese anti-trust agencies

In May 2014, InterDigital settled anti-monopoly charges with the Chinese National Development and Reform Commission (“NDRC”). As a condition for terminating the investigation, InterDigital made the following commitments regarding the licensing of its patent portfolio for wireless mobile standards to Chinese manufacturers of cellular terminal units, as follows:

- Offer a global license for its standard essential patents only;

- InterDigital will not require that a Chinese manufacturer agrees to a royalty-free, reciprocal cross-license of the Chinese manufacturer’s similarly categorized standard-essential wireless patents;

- Binding arbitration before commencing exclusionary action or injunctive relief: InterDigital will offer Chinese manufacturer (with whom it is not able to agree global royalty rates for its SEPs) the option to enter into expedited binding arbitration under fair and reasonable terms to resolve the royalty rate and other terms of a worldwide license under InterDigital’s wireless standard-essential patents.

C. Standard declarations and patents in China

The Wuhan court was adjudicating upon a global rate: This required it to see all possible SEP declarations made by InterDigital. I did a small declaration search. Per this search done on ETSI (ipr.etsi.org), InterDigital has made 74 declarations with China specific patents vs. 32 declarations having India specific patents. Each of these declarations have additional patents and the number is in the hundreds. It is clear that InterDigital itself considers China to be a more important market than India, and which is why more filing in China as compared to India.

One additional information that might be seen is that the declarations with India specific patents are recent: specifically 2014 onwards. This means that the affinity that InterDigital has towards filing patents in India is recent as compared to China.

Hence the court should have allowed for a determination of global royalty rate first and gone slow. It would be check mate for InterDigital if the Wuhan court issues a global license for its wireless SEPs. Adjudicating the validity, essentiality, and infringement of the same here in Delhi would then be a futile exercise.

D. Practical reasons why Chinese courts should evaluate the FRAND royalty

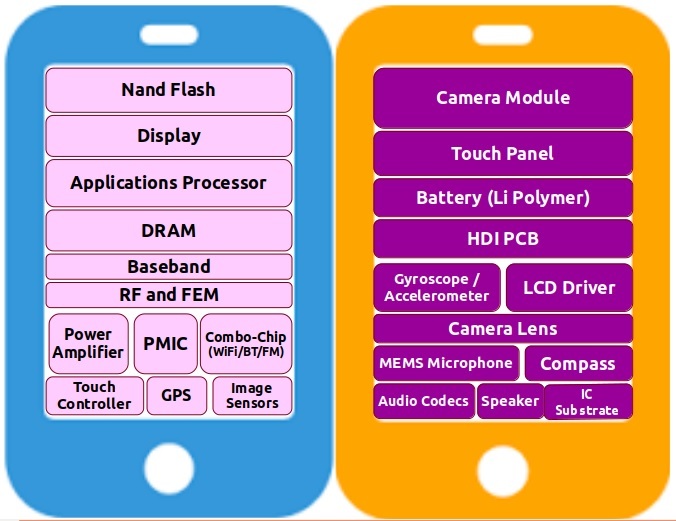

In the end I must add practical reasons why a Chinese court should determine the royalty rate, and not Indian courts. This is because the Chinese courts control the complete semiconductor ecosystem that builds all parts that go into the mobile phone: from the display to the touch pad, to the baseband processor, to the memory, to the antenna, everything is manufactured in China. Of course, there are some components that are made in India but they are at the lower end of the supply chain.

Hence, the Chinese courts have complete information as far as rate determination goes. This is important because InterDigital (and other SEP owners) does not license baseband processor providers: for good reason. They will get less royalty.

In the image below (front and back end semiconductor of a mobile phone), the only component that relates to SEP in the cellular context is the baseband processor. Other components are device specific and have no relation to the baseband processor. In other words, there is no issue before the Indian court whether the royalty demanded is FRAND. The issue before the Indian court is complicated by the presence of the confidentiality club.