[Aayush Gugnani is a Senior Status LLB candidate at Queen Mary, University of London (QMUL) with a Master’s in Economics from the University of Ottawa]

The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (‘IBC’) is normatively anchored in the objective of value maximisation of the corporate debtor’s assets, as repeatedly affirmed by the Supreme Court in decisions such as Swiss Ribbons v. Union of India and Essar Steel v. Satish Kumar Gupta. Resolution, not liquidation, is positioned as the IBC’s preferred outcome, with liquidation envisaged as a measure of last resort. Yet nearly a decade into its operation, the empirical reality of the IBC presents a paradox: average realisations of ~32% of claims (haircuts ~68%), with several large-value cases yielding recoveries barely exceeding liquidation proceeds. By late 2025, aggregate data released by the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (‘IBBI’) indicated an average haircut of approximately 68%, raising serious doubts about whether the IBC is structurally capable of delivering on its promise of value preservation.

This post advances a structural critique of one of the least interrogated features of the IBC architecture: the statutory centrality of liquidation value (‘LV’). While delays, litigation, and capacity constraints are often blamed for value erosion, this post argues that the deeper problem lies in the way LV operates as a mandatory legal benchmark. What is framed doctrinally as a “floor” for creditor protection functions economically as a “ceiling” on bids, anchoring the entire resolution process to distressed asset pricing. Through a quantitative-legal lens, and with particular reference to the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (Amendment) Bill, 2025 (‘IBC Amendment Bill’), this post demonstrates how the reliance on LV systematically undermines fair value discovery, distorts incentives, and narrows the scope of commercial wisdom that courts otherwise claim to respect.

Liquidation Value in the Statutory Architecture

Liquidation value occupies a peculiar position within the IBC. Regulation 35 of the IBBI (Insolvency Resolution Process for Corporate Persons) Regulations, 2016 (‘CIRP Regulations’) mandates the determination of both liquidation value and fair value by registered valuers, while Section 30(2) of the IBC ensures that dissenting financial creditors must receive at least the amount they would obtain in liquidation. Although the statute does not explicitly require resolution plans to exceed LV for assenting creditors, the combined operation of these provisions embeds LV as a minimum entitlement and, in practice, as the reference point around which negotiations coalesce. The jurisprudence of the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (‘NCLAT’) has consistently emphasised that valuation is a commercial matter lying within the exclusive domain of the Committee of Creditors (‘CoC’). At the same time, Courts have been reluctant to interrogate how the legal privileging of LV shapes the bargaining environment ex ante. The result is a formalist separation between law and economics: while adjudicatory bodies defer to commercial wisdom, they simultaneously enforce a statutory design that constrains the very market dynamics through which such wisdom is exercised.

NPV Erosion and the Fast-Track Fallacy

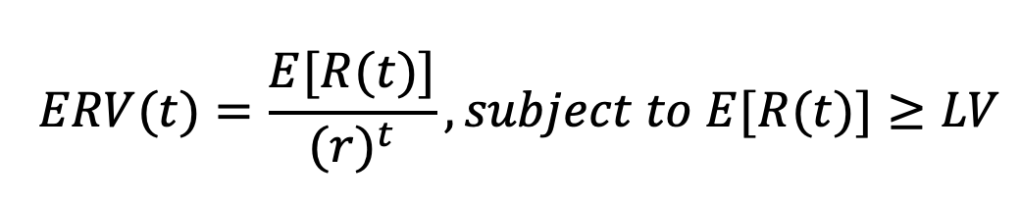

The IBC Amendment Bill introduces a 150-day fast-track resolution process for creditor-initiated insolvency resolution processes (‘CIIRP’). The legislative intuition is straightforward: delay destroys value. This intuition, however, is only partially correct. Financial theory demonstrates that time is not merely a source of value erosion but also a critical input into information generation (Grossman & Stiglitz, 1980; Myers & Majluf, 1984; Baird & Berstein, 2006). The failure to distinguish between these two effects lies at the heart of the fast-track fallacy. The expected recovery value (‘ERV’) of a resolution plan at time t may be formalised as:

where represents expected resolution proceeds conditional on information available at time t,

is the insolvency-specific risk-adjusted discount rate, and

denotes liquidation value as the legally guaranteed minimum payout under Section 30(2) of the IBC. Conventional reform discourse implicitly treats

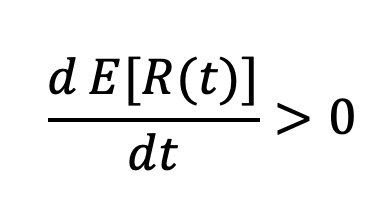

as fixed and exogenous, focusing exclusively on minimising t to reduce time value of money erosion. This assumption does not hold for going-concern resolutions. In complex enterprises, value is embedded not merely in assets but in contingent future cash flows, operational synergies, and strategic optionality. These dimensions cannot be instantaneously observed. Instead, expected recovery is endogenous to time:

at least over an initial range. Additional time enables due diligence, competitive tension, and the identification of bidders capable of extracting enterprise-level synergies. By compressing timelines ex ante, the fast-track regime risks increasing the discount-adjusted denominator while simultaneously shrinking the expected numerator. This truncation of the bidding window effectively converts a second-price auction (where bidders reveal their true valuation) into a first-price sealed-bid auction under duress, where bidders shade their bids downward to account for the heightened “Winner’s Curse” in a low-information environment.

The legal consequence is a systematic bias toward premature resolution at distressed prices. Resolution applicants, constrained by truncated timelines and heightened execution risk, rationally discount future upside and converge toward liquidation-adjacent bids. Creditors, facing statutory deadlines and the threat of liquidation, may accept such bids even where higher enterprise value exists but cannot be credibly demonstrated within the mandated window. This creates a latent fiduciary tension. Section 21 entrusts the CoC with maximising the value of the corporate debtor as a going concern. A statutory architecture that compels resolution before informational completeness is achievable but may induce outcomes that are procedurally efficient yet substantively inconsistent with that mandate. The fast-track process thus reveals a deeper contradiction within the IBC: an institutional preference for velocity that may systematically undermine value maximisation itself.

Anchoring Bias, Reservation Prices, and the Limits of Commercial Wisdom

Behavioural economics helps explain why liquidation value continues to dominate resolution outcomes even when formal timelines are met. Anchoring bias refers to the tendency of decision-makers to rely disproportionately on an initial reference point when operating under uncertainty. In the CIRP context, liquidation value, once computed under Regulation 35, becomes that anchor. Formal confidentiality does little to mitigate this effect.

Despite NCLAT’s insistence in Manish Bagrodia v. Anil Kohli (2025) that valuation reports should remain undisclosed to prevent strategic manipulation, market participants routinely infer LV through public disclosures, asset profiles, and industry comparables. From a game-theory perspective, CIRP resembles a non-cooperative game in which bidders seek to minimise their offer while meeting statutory thresholds. Section 30(2) effectively guarantees dissenting creditors their liquidation entitlement, thereby setting a credible outside option. Rational bidders therefore peg their reservation price marginally above LV, knowing that any substantial premium is unlikely to be competitively necessary. The result is a “liquidation trap,” where the protective floor for dissenters becomes the dominant equilibrium outcome for all creditors.

This dynamic systematically depresses bids below fair value. Enterprise-specific synergies, such as integration benefits, market expansion, or operational restructuring, are not fully capitalised into offers because bidders internalise the expectation that creditors will settle near LV. In effect, the statutory design transforms a collective resolution process into a constrained auction of distressed assets.

The Enterprise Value Turn and Its Discontents

Recognising these pathologies, the IBBI’s Discussion Paper on Valuation (2025) proposes a shift toward enterprise-level valuation models that incorporate intangibles, goodwill, and going-concern assumptions. This represents an important conceptual departure from the asset-centric valuation paradigm that has historically dominated Indian insolvency practice.

However, this shift introduces new layers of legal and doctrinal uncertainty. Intangibles such as brand value, human capital, and synergies are inherently probabilistic and context-dependent. Unlike land or machinery, their valuation is sensitive to assumptions about future cash flows, managerial competence, and market conditions. By asking the legal system to recognise such probabilistic wealth, the IBBI proposals challenge deeply entrenched notions of certainty and objectivity in insolvency law.

This tension is amplified by the Supreme Court’s reaffirmation of CoC primacy in Piramal Capital v. DHFL (2025), where the Court underscored that commercial wisdom includes considerations of feasibility, certainty of execution, and risk appetite. If the CoC prefers a lower asset-based bid over a higher enterprise-based bid due to perceived execution risks, courts are unlikely to interfere. Yet, this deference effectively neutralises the promise of enterprise valuation: higher fair value becomes legally irrelevant if it is deemed too uncertain.

The IBC Amendment Bill thus oscillates uneasily between numerical sophistication and doctrinal conservatism. While valuation methodologies grow more complex, the legal standards governing choice remain unchanged, leaving unresolved the conflict between maximising expected value and minimising downside risk.

Toward Risk-Adjusted Recovery Benchmarks

The central claim of this post is that liquidation value, as currently deployed, is an anachronistic metric in a modern, service-oriented economy. LV is backward-looking, asset-centric, and indifferent to dynamic restructuring potential. Its continued dominance reflects an implicit preference for certainty over value, a preference that may be defensible in liquidation but is fundamentally misaligned with a resolution-centric regime.

A more coherent approach would involve replacing static liquidation floors with risk-adjusted recovery benchmarks. Such benchmarks would account for probability-weighted outcomes, sectoral conditions, and firm-specific restructuring potential. Rather than guaranteeing dissenters a fixed liquidation entitlement, the law could mandate disclosure and justification of deviations from enterprise net present value, thereby shifting the focus from minimum payouts to expected value maximisation.

Judicial doctrine would also need recalibration. Deference to commercial wisdom should not entail blindness to structural distortions embedded in statutory design. Courts could, without second-guessing business decisions, require CoCs to demonstrate that their choices reflect a reasoned assessment of enterprise value rather than mechanical reliance on liquidation surrogates.

Conclusion: Beyond the Arithmetic Floor

The IBC’s valuation paradox lies in its reliance on an arithmetic floor that systematically constrains value discovery. The 150-day fast-track experiment, while well-intentioned, risks entrenching fire-sale dynamics unless accompanied by a doctrinal shift toward enterprise net present value and risk-adjusted valuation. Without such a shift, the IBC will continue to function as a sophisticated liquidation mechanism masquerading as a resolution framework. As India approaches the second decade of the IBC, the challenge is no longer one of speed or capacity alone, but of conceptual design. If value maximisation is to remain the IBC’s animating principle, the law must move beyond liquidation value, not merely in rhetoric, but in structure.

– Aayush Gugnani