Software such as this ‘SAB Tool’, in the online testing industry, generally more closely monitor the computer that the exam is being taken on to ensure you are not running other software in the background, such as, for instance, screen recorders, other web search utilities, calculators or cheat sheets (see a more detailed technical explanation below in: Why the SAB is important).

After the NLAT faced criticism about how exclusive access to Windows OS made the exam less accessible, NLS announced that the NLAT would also be available to MacOS, Linux and Android operating systems (OSs), purely via a web browser.

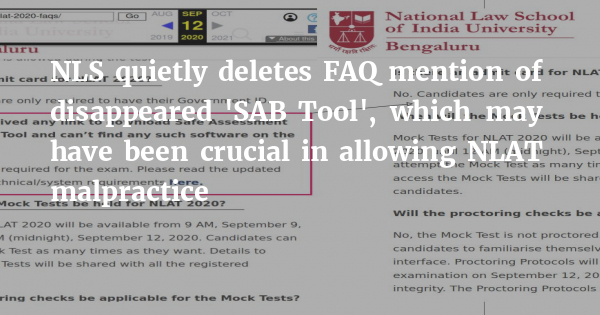

However, at the same time, it appears to have also dropped the requirement for the SAB Tool, and point 15 about this had disappeared from the latest version of the technical requirements, which is the version currently uploaded on the NLS NLAT page.

An issue of communication

Besides the SAB Tool issue, part of the problem with the NLAT has been unclear communication.

Although NLSIU had often been admirably prompt and responsive in trying to answer candidates’ questions, as well as issuing regular press releases and updates on its microsite, one problem was the plethora of communication channels, each of which carried different pieces of of the whole.

NLSIU Bangalore had been primarily answering many queries of candidates and also journalists by updating its FAQ page.

But some of the bigger changes and announcements also made its way to NLS’ official social media channels, such as Twitter and Instagram; only the most important announcements (like exam timings, re-takes or lodging complaints against the exam) were pushed to candidates via email.

And on top of that, the homepage of the exam portal, at admissions.nls.ac.in, continued hosting PDFs of fairly important announcements about the exam and an archive of press releases.

Frequently mixed up questions

The FAQs in particular, proved a pain for candidates in practice due to the terrible design of the page. Say a candidate would visit the page seeking to find out the latest updates, there was no chronology in what was most recent in what-soon-grew to 63 individual frequently asked questions.

Instead, you would have to click on each sub-sections in turn (now having grown to 10 in number) and then browse through each of the unordered subsets of those 63 questions trying to spot any new additions, modifications or changes to the wording or details in existing questions, and so on.

On the bright side, it would have been great practice for the reading comprehension section and also preparation for the reality of much law firm practice at the most junior (and sometimes also more senior) levels.

But even law firms usually use software to compare the changes between different drafts of contracts, which is what we started doing with the FAQs.

Indeed, this jumble of FAQs and the practical inability to figure out what’s new without getting a headache or software, was the main reason we had launched our first live blog of the NLAT on 8 September.

We had hoped to be able to communicate to candidates all important or interesting changes to the page they might have missed, to make their life slightly easier at such a stressful time.

And since we were still checking up on the page, today we had received the alert that NLSIU had removed something from its FAQ page.

Why the SAB was important

We had asked NLS several times since Saturday to identify the candidate who had livestreaming to us via Zoom, but understand they have neither been able to do so nor could the browser-based exam software record information that would have allowed them to do so.

Browser-based exam security (i.e. locked down browser) is online software that is limited in protecting the integrity of exams. While exam takers are prevented from performing certain actions like copying or printing webpages or visiting other websites, there is nothing that prevents them from employing tactics that effectively bypass the exam browser’s security measures altogether.

Using virtual machine software, or “VMware”, is just one of the many tactics in which the security of locked down exam browsers can be compromised. Virtual machine software allows computers to run multiple operating systems over a single physical host computer [1], which is what most exam browser software is intended to prevent. This method can be made all the easier for exam takers with websites like YouTube and Reddit that can offer step-by- step instructions on how to bypass an exam locked down browser’s security with VMware.

There are also documented instances of exam takers typing a URL into a text-only answer box within the exam locked down browser itself, that is then automatically hyperlinked. Exam Takers are able to click on the hyperlink to open a separate browser tab, opening another door for cheating [2].

While specific software tools are also unlikely to be foolproof, they make it considerably more difficult for candidates to circumvent an online test that is served via a standard web browser.

As it was held, the NLAT test was fundamentally in an identical position to any other website, such as LegallyIndia.com.

And while it is possible to capture some fairly advanced and unique information about your system (including the keys you press while in the browser window, where your mouse moves, your current screen resolution, some details about your operating system and browser, including potentially the plug-ins that are running in your browser), that information ultimately ends where your browser ends.

This means that (fortunately) neither Legally India nor any other website can find out what is open in the other tabs on your browser, short of actually hacking your system. Nor can a website know whether you are currently running other software on your computer, including Zoom, Microsoft Word, Skype.