The Delhi High Court’s August 21 order in Dabur India v. Emami has grasped the attention of the IP community in the country. Setting aside the Single Judge’s order, the court held that the appellant should have been allowed to file a response opposing the interim injunction application. One of the key considerations for this order was the appellant’s use of the mark before the institution of the suit. Later, the Single Judge in another case (Silvermaple v. Dr. Ajay Dubey) acknowledged the Division Bench’s finding on granting an opportunity to the defendant to file a response. Discussing the significance of this development, we are pleased to bring to you a post by SpicyIP intern Tejaswini Kaushal. Tejaswini is a 3rd-year B.A. LL.B. (Hons.) student at Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University, Lucknow. She is keenly interested in Intellectual Property Law, Technology Law, and Corporate Law

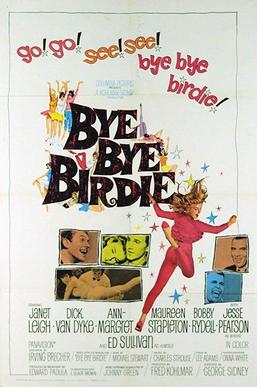

Bye Bye Ex-Parte Interim Injunctions? Navigating Denial of Ex Parte Injunction in Light of the Dabur-Emami Decision

Tejaswini Kaushal

The Delhi High Court has become a trendsetter, having introduced a significant shift in the rules governing the grant of ex parte interim injunctions—the cases in point: Dabur India v. Emami Limited and Silvermaple v. Dr. Ajay Dubey. On a peripheral observation, the cases may seem relatively distinct in their factual matrix and consequences. However, a common thread binds them: their potential impact on the probable reduction in the number of ex-parte interim injunction orders in trademark disputes. First, it was the Division Bench in Dabur v. Emami that remanded the matter back to the Single Judge for reconsideration, holding that the appellant (Dabur) should have been allowed to file a response against the application for an interim injunction, considering its use of the impugned mark before the institution of the suit. This rationale was then acknowledged by the Single Judge in Silvermaple v. Dr. Ajay Dubey, where the court explicitly stated that the defendants would be accorded an opportunity to file the response when they had been using the mark before the institution of the suit. This post spotlights the issue of ex parte interim injunctions, analyzes these recent developments, and explores their implications for future trademark infringement cases.

Emami v. Dabur and the Subsequent Appeal

In Emami v. Dabur, the Court issued an interim order, preventing Dabur (“Defendant”) from selling ‘Cool King Thanda Tel’ in packaging that resembled Emami (“Plaintiff”)’s ‘Navratna Ayurvedic Oil.’ Justice C. Hari Shankar noted that Dabur appeared to be attempting to pass off its product as Emami’s, by intentionally copying key elements of Emami’s product packaging, which had been in the market since 1989. Consequently, the Court granted an ex parte interim injunction in favor of the plaintiff, noting they had sufficiently established a prima facie case.

Within weeks of its grant, Dabur raised concerns about the ex parte nature of the order, asserting that it had not been granted the due opportunity to present its opposing arguments since the initial hearing took place on August 7, and the order was issued on August 9, 2023, before they could respond. On August 21, 2023, a division bench of the Delhi High Court consisting of Justice Yashwant Varma and Justice Dharmesh Sharma set aside the single judge’s order, acknowledging the defendant’s concerns of being deprived of the opportunity of filing a reply to the application for ad interim injunction. It directed the single judge to reevaluate the plaintiff’s application for an ad interim injunction after allowing Dabur to present its response. This order has garnered attention primarily because a subsequent order referenced it in a similar case just a week after it was issued by the same single-judge bench that granted the ex parte injunction in the Dabur case.

Silvermaple v. Dr. Ajay Dubey: Reinforcing the Stance

In Silvermaple v. Dr. Ajay Dubey, the Court relied on the Dabur order to align its stance on ex parte interim injunctions in a trademark infringement case involving the marks “DHI” and “DFI.” The Court noted that due to the recent Division Bench decision in Dabur, it could not grant an interim injunction without allowing the defendant to file a response. The bench of Justice Shankar commented that “If the defendant has been using the impugned mark, before the plaintiff instituted the suit, then, in all but, possibly, the most exceptional cases, the decision in Dabur would obligate the Court to extend, to the defendant, an opportunity to submit a written response to the prayer for interlocutory relief, before proceeding to pass orders thereon.”

The Court observed that the Division Bench in Dabur allowed the setting aside of an ad interim injunction because the defendant’s product was in the market before the suit’s institution, aligning with the Supreme Court’s Wander Ltd v. Antox (India) Pvt Ltd decision, which granted defendants a basic opportunity to oppose interim injunction applications in intellectual property matters. The Court highlighted that cases involving defendants already in the market were handled differently from those not yet in the market, stating, “Where the impugned mark has been used by the defendant for any length of time, that sole factor would entitle the defendant to an opportunity to respond, inviting, to the prayer for interlocutory injunctive relief, before orders are passed by the Court thereon.“

Courts typically consider three factors when deciding injunctions: prima facie infringement, balance of convenience favoring the plaintiffs, and potential for irreparable harm. They often grant injunctions by summarily analysing the above criteria (discussed here), leading to hasty and superfluous injunctions that are revised at the appellate stage to correct such errors, as seen in Kewal Ashokbhai Vasoya & Anr v Suarabhakti Good Pvt Ltd., Albatross Pharma v. Cipla Ltd., and others.

Justice Shankar acknowledged that in the past, including his own decisions, ex parte interim injunctions were granted, even when the defendant had used the impugned mark. However, he stressed “that position cannot, in my considered opinion, continue, in view of the afore extracted enunciation of the legal position by the Division Bench in Dabur.”

The Significance of This Trilogy

Delhi High Court’s rendezvous with ex parte interim injunctions has been contentious. The High Court has previously done some serious back-and-forth on its stance to grant these particularly unfair forms of remedy (discussed here and here in context of patent disputes). The ongoing practice of securing favorable orders without considering the defendant’s perspective has led to a slew of issues. These include prolonged interim processes and hasty, often unjust injunctions due to a significant margin of error (discussed here, here, and here).

Speaking specifically about trademark law, the prima facie validity of a registered trademark, as per Section 31 of the Trademarks Act 1999, establishes that in legal proceedings, the registration itself is considered valid unless evidence of distinctiveness or fraudulent registration is presented. However, while registration provides prima facie validity, it does not guarantee absolute rights, and the Court may still assess the validity of the mark, especially in cases of fraudulent or dishonest registration, making ‘actual use’ and ‘prior use’ essential factors in such assessments.

In the current landscape, the increasing prevalence of interim injunctions and the uncertainty surrounding their issuance are eroding their “exceptional” character. In the case of Ramrameshwari Devi v. Nirmala Devi, the Supreme Court had noted, “Experience reveals that ex-parte interim injunction orders in some cases can create havoc and getting them vacated or modified in our existing judicial system is a nightmare. Despite such court advisories to exercise caution, it is unfortunate that this practice is still overly frequent, given the highlighted issues. Nevertheless, this stance seems to be changing for the better and offers hope that the Court’s words of caution will no longer be thrown to the wind but will rather be actively applied.

Through this order, the court has established the groundwork for the defendants to claim an opportunity to explain their position. This mandates the court to make an informed decision on whether an injunction should be granted or not. Importantly, this process does not dilute the assessment of the plaintiff’s claim in any manner and adheres to the true nature of injunction orders, which is to ensure equity.

This development signals a more balanced approach by the Court regarding ex parte interim injunctions to curb unfairness and protect defendants from undue harm. It marks a much-needed improvement upon the ambiguous judicial stance on ex parte interim injunctions.